FLOOD DAMAGE:

Evolving

laws and policies for an ever-present risk

J. David Rogers,

Ph.D., P.E., R.G., C.E.G., C.HG.

Karl F. Hasselmann Chair in Geological Engineering

Department of Geological Sciences & Engineering

Missouri University of Science & Technology

129 McNutt Hall, 1400 N. Bishop Ave.

Rolla, MO 65409-0230

INTRODUCTION

Flooding is a natural geologic

hazard that will always be with us. In

fact, virtually all the sediment deposited upon the continent are

deposited on well-defined flood plains, which also enabled our agricultural

development. Those areas have since

become prime real estate and support a large percentage of the population. This article provides a brief introduction to

the reasons for floods, their periodicity, the National Flood Insurance Program,

and the problems associated with estimating areas of likely inundation and

relative risk; revealed by the repeat occurrences of so-called “100-year”

floods with seemingly increasing frequency.

The balance of the article contains examples of the various theories

of liability presently applied to litigation in the United

States associated with common flood hazards,

drawing in large part from legal cases in California.

HISTORICAL

CONTEXT

The nation’s first locally-controlled

flood control agency was the Miami Conservation District, formulated in 1913

in the wake of the disastrous Dayton, Ohio flood of that same year, which

killed 600. The city fathers asked renowned civil engineer

Arthur E. Morgan to come to Dayton

and have a free hand in devising such engineering schemes necessary to prevent

such a tragedy from ever occurring again.

Morgan was a man with purpose and drive, who went on to become the

first director of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1934. Morgan astounded everyone by removing those

portions of downtown

Dayton which had encroached on

the historic channel of the Miami River. He enlarged the river channel and built enormous

levees. Then he then built three “flood

control dams”, or retention basins, on the Miami River

upstream of Dayton. Morgan also issued an edict which prevented

the reservoirs from ever being filled, to prevent hydropower and recreation

interests from becoming tempted to lessen flood storage and thereby, negate

the dam’s fundamental purpose (Morgan, 1952).

Morgan’s stringent flood control

measures have proven themselves to be prophetic time and again, as flood control

infrastructure in the United States

has repeatedly failed because of political and economic compromises to create

“multi-purpose reservoir projects”, to gain a broader base of support for

funding of dams. In the 1997 New Year’s

floods in northern California

the unprecedented number of dams and flood control infrastructure was unable

to protect the lower Sacramento

Valley because operators had gradually

lessened the flood storage capacity of each reservoir in order to promote

enhanced power generation, greater summer storage and recreation capacity.

Morgan’s 1913 warnings about the dangers of multiple-use reservoirs

were fulfilled, and California

suffered more than $4 billion in flood damages, despite having some of the

world’s largest flood control dams in place.

A fundamental problem in forecasting

flooding has been the absence of adequate flow records. In his last article for the American Society

of Civil Engineers, Professor Ven Te Chow of the University

of Illinois reminded fellow engineers

that in order to adequately predict a 100-year recurrence interval flow event,

one would need 1000 years of hydrograph records (Chow and Takase, 1977).

In most instances, project floods are based upon inadequate flow data,

extrapolated well beyond the range of scientific certainty and subject to

all kinds of flow adjustments, as discussed later.

Perhaps the best appreciation

of how poorly we predict so-called “maximum flood events” are some of the

flow records in California. The lower Sacramento River

recorded nine “100-year floods” during the 20th Century, in 1907,

1909, 1936, 1955, 1964, 1982, 1986, and 1997.

Southern California purported to have received

seven such events, in 1914, 1916, 1938, 1969, 1993, 1995/97 (depending on

location). At the time these extreme

flow events occurred each appeared “unprecedented”. Some of the increase in peak flow was likely

due to channelization and man-induced activities associated with agricultural

development and urbanization. It is

obvious that the estimates of 100-year recurrence frequency will continue

to evolve as more flow data is collected.

Following the disastrous 1927 and 1937 floods of

the lower Mississippi and Ohio

Valleys the U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers began to develop methods by which levees could be evaluated, engineered

and strengthened. This pioneering work

culminated in a better understanding of the limitations of man-induced flood

control and river training than had previously been appreciated.

By the late 1950s flood inundation models began to evolve which were

computerized in the 1970s and 80s to calculate inundation areas for the probable

maximum flood, as well as 100-year (1 chance in 100 of occurrence) and 500-year

(1 chance of 500 of occurrence) frequency floods, commonly used on government-sponsored

flood maps. But, because parcels are

developed in a piecemeal fashion, each one only a small part of an immense

watershed, the so-called “project flood” evolved.

A “project flood” is that frequency of occurrence felt to be within

economic reasonableness for the size and value of development contemplated. For government infrastructure, the “project

flood” value most commonly selected is half of the probable maximum flood,

and is usually something between a 50-year and 100-year recurrence frequency

event. Developers of small parcels

oftentimes attempted to install drainage infrastructure with between 10-year

and 25-year recurrence frequency, leading to a heterogeneous mix of drainage

improvements which are seldom, if ever, compatible.

In 1969 the Federal Emergency

Management Agency (FEMA) began to administer a Federally-mandated National

Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Act of 1968 (42 U.S.C. 4001-4128, and Supp.

III 1985). This program sought to socialize

the burden for flood damage between those individuals who actually live in

flood-prone areas, and sets rates according to relative risk of occurrence,

based on computer simulations of flooding.

For example, people living within the 100-year frequency inundation

area are charged at a higher premium than those above the 100-year line, but

within the 500-year recurrence frequency level.

Damaging floods occurred in the

San Francisco Bay Area in 1955/56, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1967, 1969, 1973, 1982,

1983, 1986, 1993, 1995 and 1996/97. Five of these events were espoused to be 100-year

recurrence frequency events. This is

doubtful. A 100-year recurrence frequency

suggests that the river or stream flow has one-chance-in-100 storm events

of occurring at any given time. But, it’s not that easy. Other factors play a large role in determining

how high flood flows get against the bank at any given location. Some of these factors are listed in Table 1.

Table

1

Common

factors affecting accuracy of flood predictions

|

Factor |

Description |

|

Antecedent moisture |

How much rain has already been absorbed

by the ground, season-to-date. The

more saturated the ground surface, the greater the runoff from any

given storm. Landscape watering

can also lead to increased levels of antecedent moisture. |

|

Localized cells of intense precipitation

|

Very intense bursts of moisture in upland

areas can cause localized flooding and destructive debris flows which

clog drainage inlets, culverts, etc, which then leads to flooding

|

|

Duration of storm events |

The longer storms stall over any given

area, the greater the flooding |

|

Changes in vegetation within the watershed |

Changes in land use (such as grazing)

and vegetation will lead to changes in the time-to-concentration of

runoff to local creeks and rivers.

|

|

Development of the watershed |

The more hardened surfaces, such as

roofs, walkways, pavements and lined storm drainage channels, the

greater the peak runoff. A

400% increase is not unusual, commonly leading to down cutting of

unimproved channels |

|

Unnatural constriction of flow |

The placement of hardened improvements

in channels, such as culverts, rip rap, retaining walls, or; natural

impediments to flow, such as landslides, eroded soil, trees, organic

debris and natural storm-laden debris, invariably cause localized

hydraulic chocking of channels, leading to tail water inundation of

previously un-flooded areas |

|

Changes in weather patterns |

Frequency and probability-based flood

flow assessments are based upon the assumption that weather patterns

are essentially unchanging. Data

collected since 1849 would suggest otherwise, weather patterns are

always changing. |

|

Mistakes in flood plain management |

Whatever can go wrong in routing floods

via use of planned releases from flood control reservoirs, eventually

will. |

|

Failure of flood control infrastructure |

Despite the best intentions, infrastructure

elements, such as levees, dam spillways and conduits, can fail, most

often during peak usage. Levees

are particularly sensitive to duration of flood flow |

|

Accuracy of topographic information |

The accuracy of topographic information

within the watershed being studied will exert keen influence on the

areas predicted for inundation |

|

Accuracy of channel roughness estimates |

Channel hydraulics assessments are dependent

upon estimates of channel roughness, which are highly variable in

unimproved channels, and subject to change, depending on frequency

and depth of flows |

|

Accuracy of input hydrology |

Flow assessments are only as good as

the estimates of precipitation upon which they are based. An array of antecedent moisture levels needs

to be evaluated in order to make conservative predictions of flow.

|

|

Accuracy of the computational methodology

chosen |

A

wide array of computational models exists, the most commonly employed

being HEC-2, developed by the Army Corps of Engineers. However, flow predictions are built upon the

detail and accuracy of input information, such as the number of channel

cross sections.

|

A careful study of the factors

listed in Table 1 should present the reader with sufficient reason to suspect

that most of these factors affect every stream in developed watersheds of

the United States.

Massive changes in vegetation, land use and weather patterns have led

to increased downcutting of channels in coastal California,

with the largest watersheds responding first, followed by their own tributaries

(Bull, 1991). Examples of recently

entrenched channels can be seen all over Contra Costa, Alameda

and Sonoma Counties. 25 years ago most hydrogeologists believed that

the downcutting was associated with increased development, but careful measurements

have shown the downcutting appears to be of similar magnitude within non-developed

watersheds as well; leading to the conclusion that other factors, such as

vegetation, land use and weather patterns are the real culprits (Rogers,

1988).

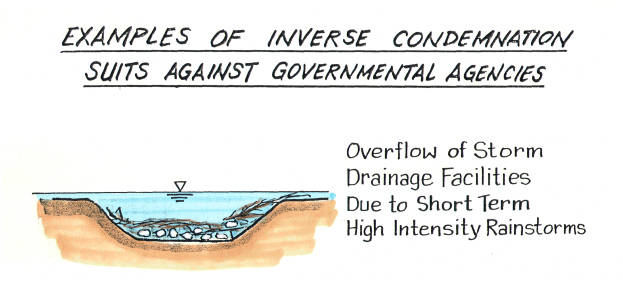

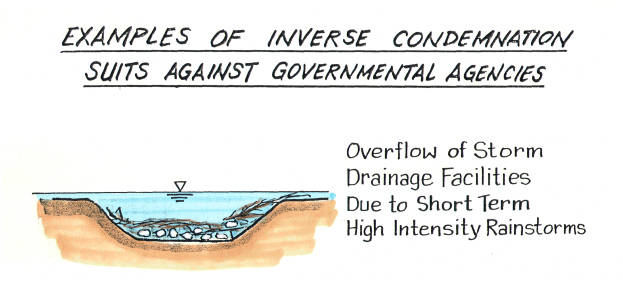

Some of the most common forms

of flood damage are presented in Figures 1, 2 and 3.

For public agencies, plugged culverts are by far the most onerous,

giving rise to inverse condemnation suits by adjoining property owners whose

properties are damaged (van Alstyne, 1969).

THEORIES

OF LIABILITY APPLIED TO FLOOD DAMAGE

Damage

Ascribable to Unchanneled Surface Waters

California

case law has generally stated that liability may follow from damage by naturally‑occurring

run‑off, or surface waters only if the

upper landowner causes the damaging flooding by his unreasonable or arbitrary

acts. The most cited case is the area

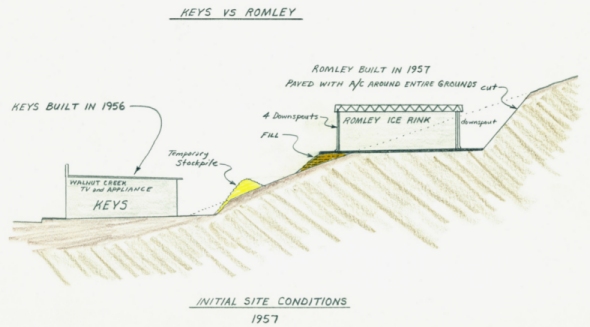

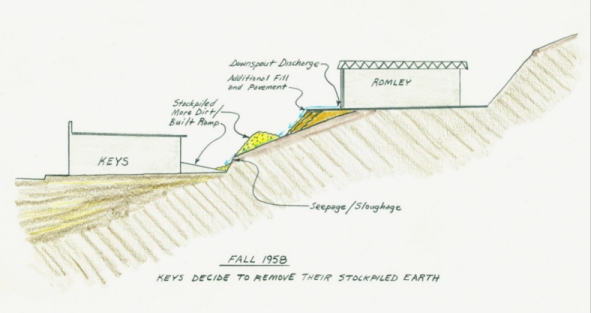

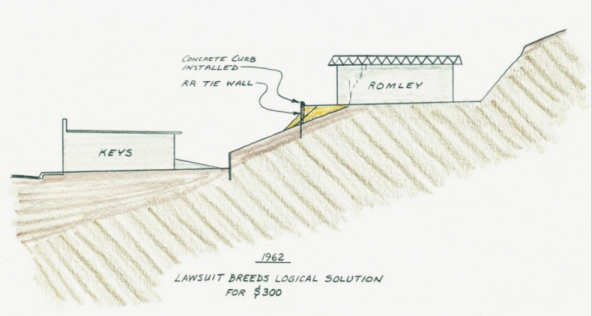

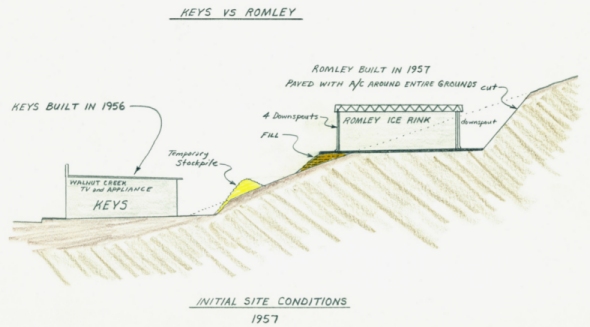

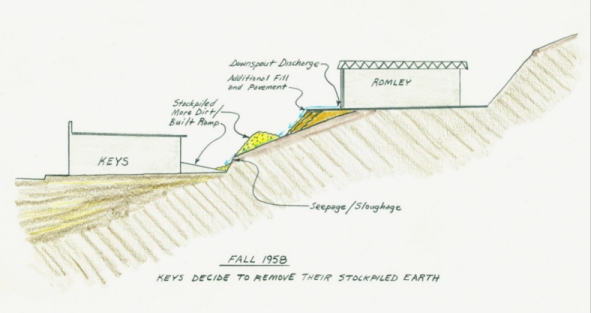

of surface run‑off is Keys versus Romley (1966) Cal.

2d. 396. In this case, the owner of

an electronics store in Walnut Creek

(Keys) was happily minding his own business until an adjacent, uphill property

was developed into an ice rink by Romley.

The run‑off from Romley's roof and parking areas was subsequently

concentrated on the newly‑filled slope above and behind Keys' store. When severe rains came, soil slumped on the

newly‑filled slope and Romley's run‑off was preferentially directed

into Keys' store, causing him damage (see Figure 4).

Keys sued and eventually prevailed,

therein making this case the pre‑eminent example of the so‑called

"Law of Reasonable Use" wherein

all owners of improvements must act in a reasonable and competent manner

to combat rainfall‑induced run‑off.

"Common

Enemy Doctrine"

The common enemy doctrine evolved

from the same sort of flood cases which gave rise to the Natural Watercourse

Rule (discussed later). The difference

lay in surface or near channel "improvements", such as protective

barriers, dikes, and levees which offer protection from flood water damage.

The common enemy doctrine held that such barriers could be constructed

with immunity, even if the barrier subsequently caused the diversion of flood

waters onto the land of others.

The early California

courts felt this exclusion necessary so as not to punish the "good faith

improver" who installed his flood control works or barriers. After all, why should an adjacent neighbor,

who fails to spend the money necessary to protect his property, be able to

punish those who do? The common enemy

doctrine was a way of encouraging adjacent landowners to make like improvements.

The landmark plaintiff cases were generally made against reclamation

districts and railroads.

Figure 4

- In the case of Keys vs Romley (1966),

the Doctrine of Reasonable Use was adopted to pertain to collection and conveyance

of surface waters

on improved parcels.

The uphill owner, Romley had constructed his improvements in a manner which

is served to unnaturally concentrate run-off

onto a cut/fill slope

above and behind Keys’ store. Asphalt curbs, drop inlet catch basins, and

piped outflow were required to mitigate the problem.

Figure

5

The

“common enemy doctrine” reduces the potential liability of a “good faith improves”

who takes reasonable action to prevent or retard future flood damage, even

if said improvements promote future damages downstream.

However, the "common enemy doctrine" does not relieve landowners of liability

for negligence when his diversion of surface water damages another's property.

In 1987, the California Court of Appeals reversed a lower court decision

that had upheld the common enemy doctrine. The CEB Real Property Reporter (1987) summarized

this important case as follows:

Linvill v Perello (1987) 189 CA3d 195

Both

parties' lands were adjacent to a natural watercourse which periodically breached

its banks during times of flood and caused waters to flow across the properties

without significant damage. Defendants

then built a levee on their land which directed all the water across plaintiffs'

property, causing personal injury and property damage. Plaintiffs sued for negligence. The trial court granted defendants' motion for

summary judgment based on the common enemy doctrine, which allows a landowner

to build protective barriers against flood waters on his property, even if

the barrier then diverts water onto the land of others (see Figure 5).

The

court of appeal reversed. Under CC 1714, one is responsible

for injuries caused by want of ordinary care in the management of one's property.

This principle also applies to natural conditions on land.

Sprecher v Adamson Cos.(1980) 30 C3d 358. Under Rowland

v Christian (1968) 69 C2d 108, an exception to this rule should not be

made unless there is a clear public policy reason to do so.

The

court concluded that there is no policy reason to create an exception to the

rule for surface waters, as the common

enemy doctrine does. Imposing this

rule will not necessarily prohibit the development and improvement of land

along rivers. The California Supreme

Court has declared that the utility of the possessor's use of land is a relevant

consideration in determining the propriety of his alteration of the flow of

surface waters, see Keys v Romley

(1966) 64 C2d 396. The court also noted

that the previous supreme court case upholding the common enemy doctrine with

regard to flood waters, Clement v State

Reclamation Bd. (1950) 35 C2d 628, was decided 18 years before Rowland and, therefore, is probably no

longer applicable.

Old

Civil Law and the Natural Watercourse Rule

In basic terms, the “civil law rule” developed

within California sought to

recognize the servitude of natural drainage courses: the lower owner must

accept drainage onto his land, and the upper owner has no right to alter drainage

so as to increase the downstream burden. But, courts quickly appreciated the Pandora’s

Box allowed by such a theorem if every inhabitant of a given watershed normally

and naturally subject to flooding is allowed to file a cause of action against

upstream parcel owners who they allege have altered the flow.

Beginning with San Gabriel

Valley Country Club vs. County of Los Angeles (1907) 182 Cal.

392, courts granted immunity to upstream landowners who make drainage improvements

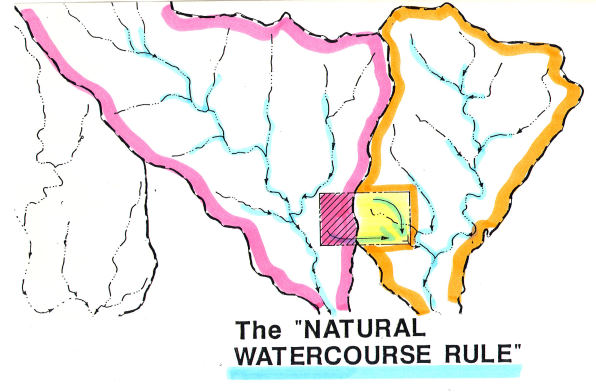

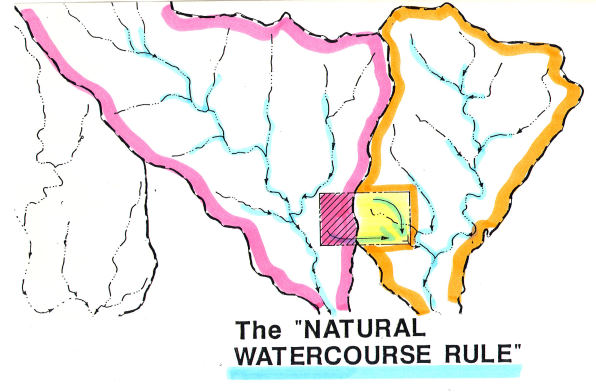

as long as those improvements conform to three basic premises:

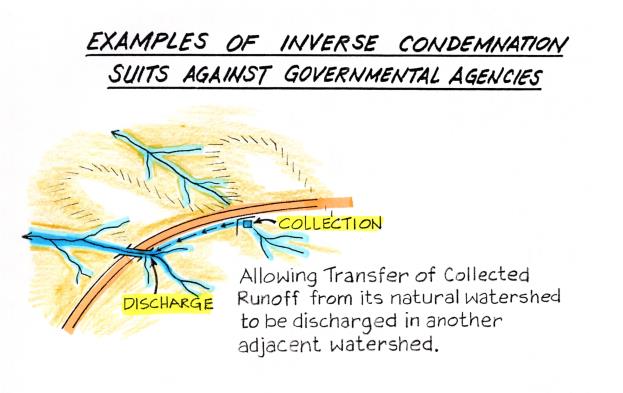

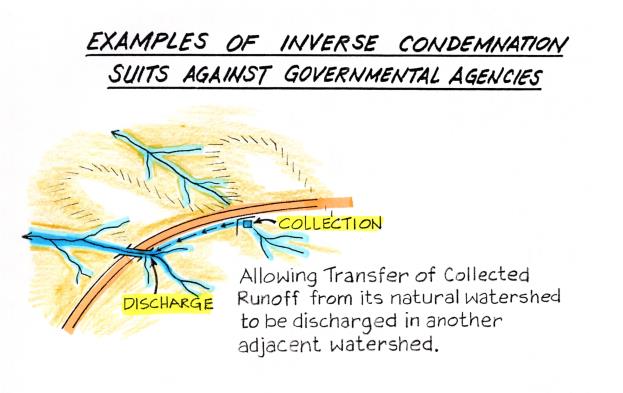

1. They have not diverted run‑off out

of its pre‑development, or natural

watershed (see Figure 6);

Figure 6

- Protection under the legal theorem of the “Natural Watercourse Rule”

is violated when surface waters within

a natural within a

natural watershed are collected and unnaturally discharged in another watershed.

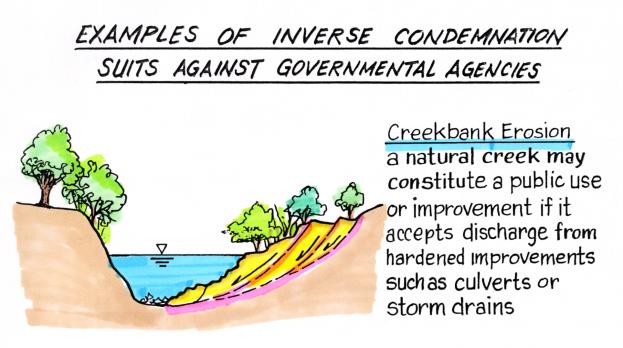

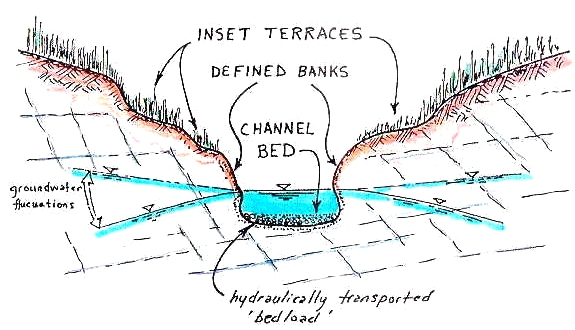

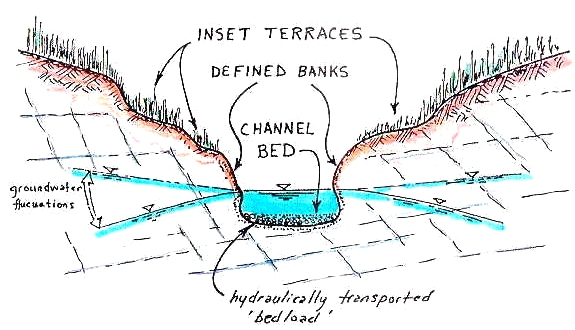

Figure 7 - A

natural watercourse is defined as a naturally-occurring stream, river, creek,

runs, or rivulet. The stream need not

flow continuously, it may sometimes

be dry. It must be something more than mere surface run-off over the face of the land.

2. Run‑off is conveyed to the natural

stream course (with bed and bank) that the run‑off would have naturally

flowed to (see Figure 7; and

3. The upstream improver has not created

unnatural diversions, obstructions, or

trespassed into the high‑flow channel cross section which could be construed

as unreasonable, negligent, or worthy of trespass (see Table 2).

The liability relief once spelled

by the old Natural Watercourse Rule

cannot be understated. Countless flood

cases are caused by increases in peak stream flow ascribable to upstream development.

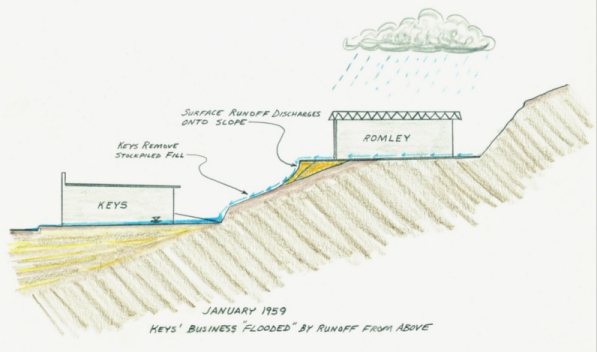

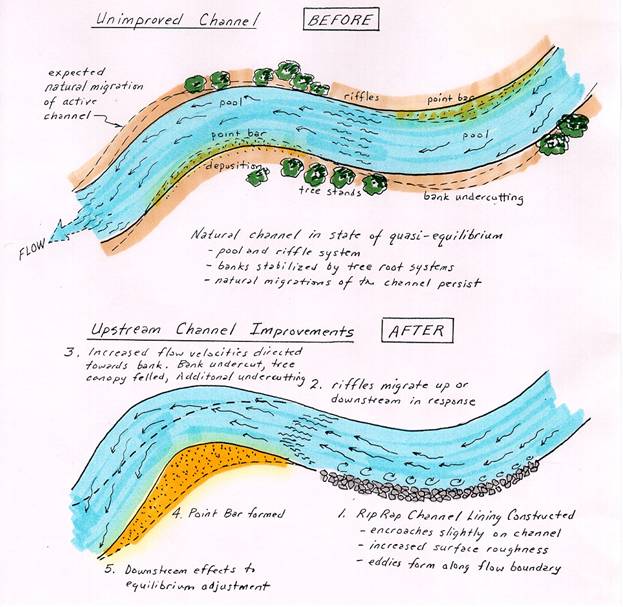

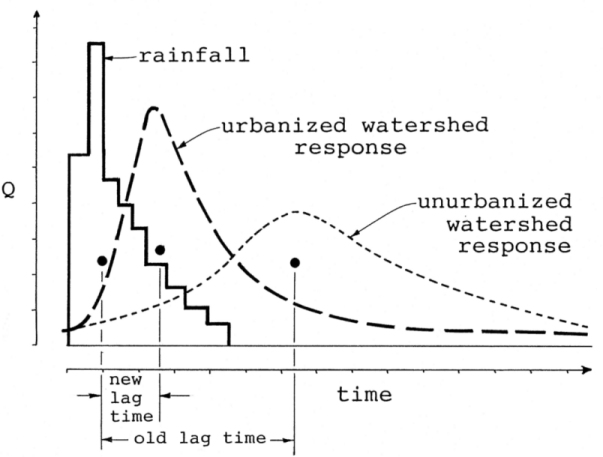

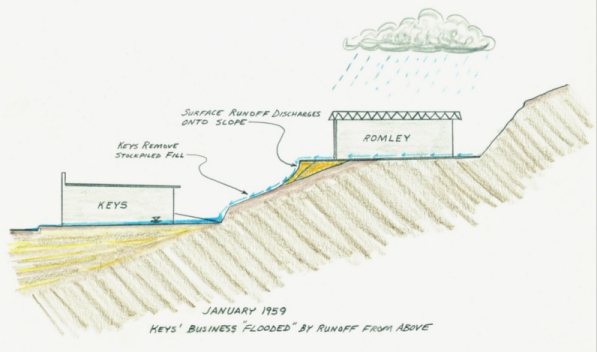

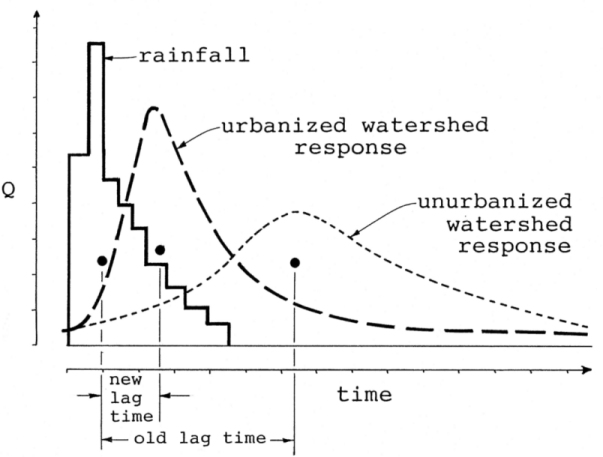

As shown in Figure 8, upstream improvements such as impermeable surfaces

(pavement, roofs, gutters, culverts, etc.) bring the run‑off to a natural

stream course much more quickly than in an unimproved

or "agrarian" state.

The Natural Watercourse Rule had

been challenged unsuccessfully in a large number of cases (see San Gabriel

Valley Country Club {1920} and Archer {1941}), but was eventually

overturned in the Locklin vs Lafayette,

et al case in 1993. Synopses of these

cases follow:

San Gabriel Valley Country Club vs County of Los Angeles (1920) 182 C.392.

"The improvements must follow

the natural drainage of the country. If

the water is diverted out of its natural channel and discharged into a different

channel or upon neighboring land, the diverter is liable to the owner whose

land is injured."

Archer vs City of Los

Angeles (1941), 19 c. 2d 19

Archer lived by a lagoon near

the ocean. Tributary watershed to the

lagoon area was urbanized, thereby decreasing run‑off infiltration and

time to concentration and increased peak flow thereby ensued. A non suit judgment was granted in favor of

the City. Judgment Statement said "...a

lower owner has no right of redress for injury to his land caused by improvements

made in a stream for the purpose of draining or protecting the land above,

even though the channel may be inadequate to accommodate the increased flow

of water resulting from the improvements."

In light of the older, established

court decisions, it appears clear that an upper landowner may act with relative

impunity in collecting and discharging water from his property into a natural

watercourse ‑ even though the

additional water may exceed the capacity of the downstream channel.

In addition, it is equally clear

that an upstream owner may improve the watercourse to facilitate drainage

flow from his property, and the fact that said improvements artificially increase

the quantity or accelerate the velocity of the stream flow within the channel

is an insufficient basis of which to impose liability.

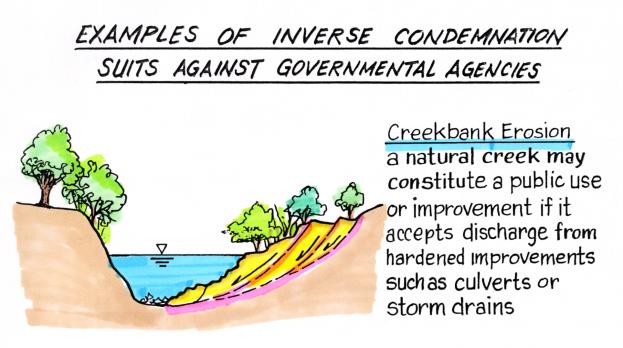

Locklin vs City of Lafayette

(1992) 11 CA4th 1, 13 CR2nd 889

A group of property owners living

along lower Reliez Creek, an unimproved channel, alleged in an inverse condemnation

action that the City, County, Walnut Creek,

BART and Caltrans benefited from the channel’s use as a quasi storm runoff

channel, and that because of increased flow due to public improvements, their

channel had been unnaturally eroded. In

1988 the trail court granted motions for a nonsuit for 4 of the 5 defendants,

citing the Natural Watercourse Rule, which then allowed the establishment

of drainage improvements within a natural watercourse, even if said improvements

cause increased runoff downstream. This decision was affirmed by the appellate

court. The lower courts felt that the

plaintiffs had not demonstrated that the public agencies had exercised the

kind of control necessary to convert the creek into a public improvement,

despite accepting flows

from hardened improvements located upstream.

In February 1994 the case then

came before the California Supreme Court (7Cal 4th 327, 1994), who partially

overturned the decision, there by rescinding the natural watercourse rule. The Supreme Court eliminated the immunity afforded

by the Natural Watercourse Rule and instead held that anyone or any agency

can be held liable if they act unreasonably in the collection, conveyance

and discharge of surface waters. The

Court also imposed an obligation on the part of individual property owners

to take reasonable actions/precautions to protect their banks from threats

of erosion and flooding; and that, if said individuals act unreasonably, they cannot recover

for damages which then occur (similar reasoning to the common enemy doctrine,

discussed elsewhere). The Locklin

decision means that public agencies, in particular, will no longer be granted

summary judgements in flood cases involving natural channels, as had been

the case for the previous 85 years.

Negligent Diversion or Disturbance

of a Natural Watercourse

Even with the recent overturning

of the natural watercourse rule, flood water damages have always resulted

in liability if there is a diversion

of the waters onto property which would otherwise have been unaffected (see

Van Alstyne 1969, p. 454). In inverse

condemnation liability, the proximate

cause of damage is a major consideration.

In other words, was a diversion

or a negligent act a substantial cause of the alleged loss? In legal terms, the burden of "proof"

often times lies in proving that the flood‑induced damage was over

and above that which would have occurred in the absence of a structure or

activity that gave rise to an unnatural diversion or protuberance of the natural flow regimen. Those factors most often cited as being Aunreasonable behavior@ inexpert testimony are summarized

in Table 2.

TABLE

2

Activities

Undertaken Within Channels Commonly Deemed “Unreasonable”

|

Collecting surface waters from one natural

watershed and concentrating into another |

|

Concentrating discharge in any manner

of hardened improvement, such as lined channel, culvert or pipe, in

such a manner as to cause unnatural increase in runoff velocities

and/or concentration of runoff quantity that actually leads to unnatural

or accelerated erosion, which occurs as a direct consequence

of said improvement |

|

Causing unnatural concentrations of

surface flow due to physical encroachment on an unimproved (natural)

channel within the FEMA 100-year recurrence interval flow area |

|

Causing unnatural bank erosion through

excavation or dredging of the channel substantially outside the centerline

(thalweg) of flow |

|

Creating obstructions to flow by blockage,

dumping or inadequate diversion of any natural channel or swale, or

of an improved channel (common in construction related activities) |

|

Failure to maintain hardened drainage

improvements within a reasonable time interval of learning that flow

capacity has been hindered or impaired by any manner of hazard, such

as catchment of organic debris, siltation, accidental mechanical damage

or weathering |

|

Negligent design of channel improvements

|

Two principal cases pertaining

to activities within channels are most often cited. Flooding ascribable to inadequate runoff collection system is

not negligence per se, as described in the Tri-Chem decision. The Ektelon and Linvill cases involved alleged

negligent activities within channels, and thereby came to be judged under

doctrines of reasonableness now commonly associated with surface water collection,

conveyance and discharge.

Tri‑Chem

vs Los Angeles Flood Control District (1973) 60 Cal.

App. 3d 309

The plaintiff owned a parcel of

naturally low‑lying ground in an industrial tract in Torrence. Run‑off from natural slopes to the south

caused run‑off to collect on the property. One cross street culvert served to drain the

plaintiff's property (see Figure 8). The

capacity of the drainage trunk line into which the plaintiff's culvert entered

was only that expected from a 2 or 3‑year frequency storm, the mouth

of such line having been built in 1940. In

January 1969, during a 17‑year recurrence frequency storm, the capacity

of the trunk drain line was exceeded by a factor in excess of 200%. This increased factor resulted in the breaching

of a sandbag dike, which resulted in the flooding of the plaintiff's property.

The Court upheld the Flood Control District's assertion that it was

not liable for flood damage on the

basis that its conduct, in and of itself, was not a proximate

cause of the plaintiff's damage. The

City and Flood Control District were further able to contend that they were

not negligent in maintaining their portion of the

flood control system. The Court

found that, although the flood control improvements were aged and undersized,

they still constituted an improvement

which provided benefit to the plaintiff, without which flooding would have been worse.

Ektelon

v City of San

Diego (1988) 200 CA3d 804

A downstream riparian owner sued

the City of San Diego and others

for flood damages caused by the City's construction of upstream flood control

facilities. The trial court granted

defendants' motion for nonsuit, but the court of appeal reversed.

The trial court had relied on

Archer v City of Los Angeles (1941)

19 C2d 19. The court in that case held

that an upstream owner is not liable for injuries resulting from improvements

made to protect the upstream land even if the channel is inadequate to accommodate

the subsequent increased flow of water. In a later case, however, the California Supreme

Court held that an upper landowner must act reasonably with regard to the

discharge of surface waters from his land.

Keys v Romley

(1966) 64 C2d 396. This principle of reasonableness applies to

stream waters as well as surface waters.

Linvill v Perello (1987) 189 CA3d 195, 234 CR 392 (10 CEB RPLR

94 (June 1987)). As a consequence of

Linvill, upstream flood control improvements are now subject to principles

of ordinary negligence. As noted in

Linvill, application of negligence principles

will not hinder the development and improvement of land along river bottoms;

a rule of reasonable conduct, which weighs the utility of upstream diversion

of flood waters against the gravity of harm caused to downstream lands, is

not inconsistent with development concerns.

Typical Hydrograph

Figure8

- Schematic representation of changes in peak stream flow due

to adjustment of a perturbed watershed. The lag time is the interval between

the mean rainfall

occurrence and

the mean run-off in response to such rainfall. The lag time can be significantly

reduced as the watershed run-off characteristics

are changed by paving

and urbanization,

vegetation change, over grazing, or weather pattern change. Most California

streams have made marked adjustments over the

past century, due,

in part,to

all of the above-cited factors. The creeks with the greatest flows adjust

first, with successively smaller tributaries adjusting more slowly, due totheir

lower

stream

power. Arid areas generally take longer to adjust than do areas of greater

precipitation and run-off. Many inverse condemnation suits seek damages

from

public agencies

on the basis of drainage improvements reducing lag time, and therein increasing

peak flows which are more destructive and erosive.

Common Sources of “fault” in

Flood Cases Involving Public Entities

In order to trigger inverse condemnation

liability a plaintiff must demonstrate some manner of preventable fault on the part of the public

entity. The burden of proof for the

plaintiff in a flood control/levee failure case normally focuses on the demonstration

of:

a. failure to

properly maintain the levee structure in such a manner that such neglect was a direct or significant factor in the levee's subsequent failure; or

b. that the levee

or its appurtenant structures were originally constructed in a negligent manner

which significantly contributed

to the levee's failure.

Allegations of negligence

in design or maintenance are usually "necessary" because they are

the only tried and true avenues of "levee liability". In order to trigger maintenance liability, some

demonstration of the levee owner's (respondent) legally imposed duty to maintain the levee will first have to be made.

Such allegations have failed on several occasions with actions involving

the L.A. County Flood Control District, having

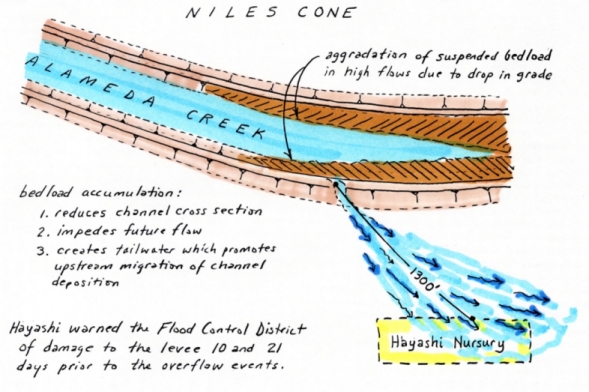

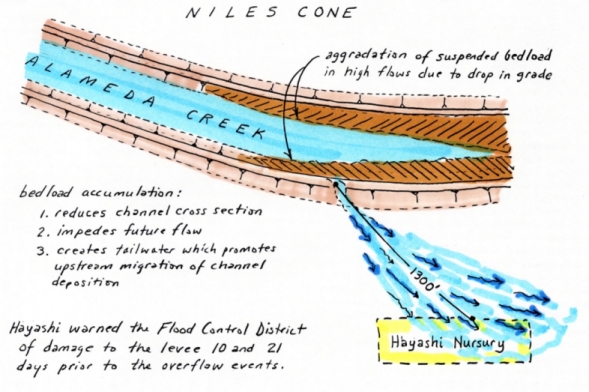

been formed by referendum in 1916 (see citations, bottom p. 587, in Hayashi vs Alameda F.C.D., (1959) 167 Cal App 2d p. 584) (shown in

Figure 9). Districts formed at later dates may have somewhat more explicit

mandates with respect to maintenance. In

the Hayashi case, Alameda F.C.D. had been formed in 1949 with a more explicit

mandate for maintenance responsibility. In

that case, the court asked:

"after

the public improvement is constructed, is the District, after notice, under

an obligation to maintain it (the levee) in such a manner so as not to injure

the adjoining property as the result of negligent maintenance?"

In the Hayashi

case, the plaintiff had notified the District 10 and 21 days prior to the

subject losses. This prior notice sealed the case, and most

subsequent cases of proven prior notice, in the plaintiff's favor.

The Hayashi case also went

on to explore some of the "common enemy" flood control doctrines

normally brought out by public agencies in their defense. These include:

a. "Under the general common law, there

can be no doubt that a landowner is responsible for damages caused by the

negligent disrepair of an artificial structure." (taken

from Hayashi)

But, it would appear

that liability is only incurred if it can be shown that reasonable maintenance would have disclosed the problem and that the

problem could have been made reasonably safe through quick and judicious repair;

or that the owner/maintainer were put on notice that a repair might be needed

and failed to heed such notice (thereby possibly being negligent).

Figure 9

- In the case of Hayshi vs. Alameda County Flood Control (1959), the plaintiff

prevailed in his flood damage suit because the District’s mandate

specifically includes

flood control maintenance responsibility. Hayashi had warned the District

of a weakened levee area 10 and 21 days prior

to

the actual breach

and the Court found the District liable for not providing reasonable maintenance

in light of the prior notice of the problem.

The Hayashi Decision (p

590) went on to state:

b. "If a structure suddenly and without

the fault of the processor becomes dangerously dilapidated, the possessor

is not subject to liability for any harm done thereby to persons outside

the land until he has had an opportunity, by the exercise of reasonable care,

to make the structures safe."

In conclusion then,

it would appear that a levee owner in

California is only liable for flood damage caused by

the negligent maintenance, construction, or permitting hazardous activities

in proximity to the levee.

Belair

vs Riverside County Flood Control District (1988) 47 Cal

3d 550

The most severe challenge to the

doctrine of proving unreasonable conduct was the recent case of Belair vs Riverside County Flood Control

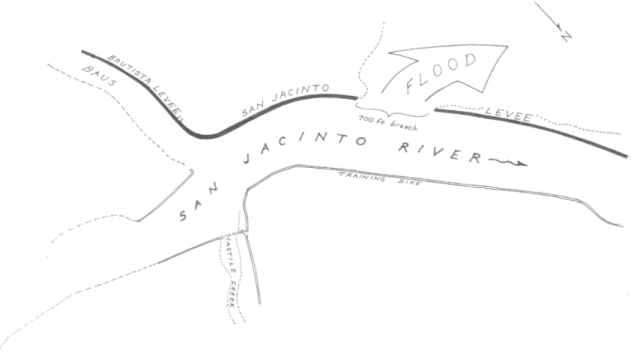

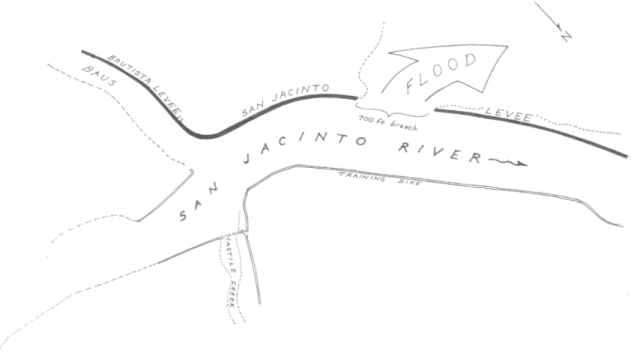

District. In 1980, a flood

control levee on the San Jacinto

River failed at a flow volume only

29% of that which the channel had been originally designed to function by

the U.S. Corps of Engineers in 1960. Parts of San Jacinto

were flooded. Various property owners

sued the flood control district and State for damages under inverse condemnation

theory. Unable to show fault on the

part of the State or the District, the plaintiffs' attempted to establish

inverse condemnation tort without fault. But,

the trial court entered judgment for defendants and the court of appeal affirmed.

The California Supreme Court also affirmed in December 1988, but on

different grounds.

The levee was designed and constructed

to contain a flood discharge of 86,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), and the

discharge at the time of breach was only 25,000 cfs (see Figure 10). Plaintiffs contended that this fact established

that the levee had failed to function within its design capacity, which was

all that they were required to prove. As

in the case of Tri‑Chem, the trial court had also found, however, that

plaintiffs' properties had been subject to periodic flooding before construction

and that the levee had not increased the risk of flooding.

On the basis of this finding, the court of appeal had held that the

levee was not the proximate cause of plaintiffs' damages (the rain was).

The supreme

court rejected the court of appeal's proximate cause analysis, concluding

that the levee was a substantial concurring cause because it was designed

to contain 86,000 cfs and it failed to function as intended. The prior flooding was not significant because

owners had been induced to improve their property in reliance on the protective

ability of the levee. The court also

held that plaintiffs were not required to prove that the levee had increased

the risk of flooding; a public improvement need not worsen a pre‑existing

hazard to give rise to liability for inverse condemnation.

Nevertheless, in a flood control

case, plaintiffs cannot rely on a simple strict liability theory. The rule of Albers v County of Los Angeles (1965) 62 C2d 250, 263 ‑ i.e., imposing liability for any actual

physical injury to real property proximately caused by the improvement as

deliberately designed and constructed ‑ is subject to the exception

established by Archer v City of Los

Angeles (1941) 19 C2d 19, 24, which recognized that, in some situations,

the state has a right to inflict damage, based on the common law right of

landowners to erect barriers to ward off flood waters (known as the common enemy doctrine). However,

a public agency engaged in the activity of flood protection must at least

act reasonably and non‑negligently.

"[The fact that a dam bursts or a levee fails is not sufficient,

standing alone, to impose liability. However,

where the public

Figure

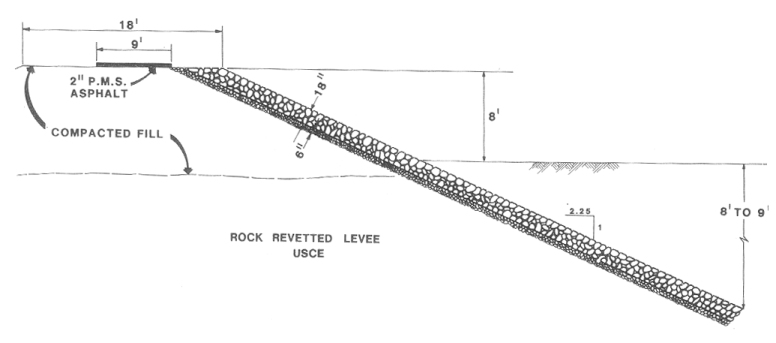

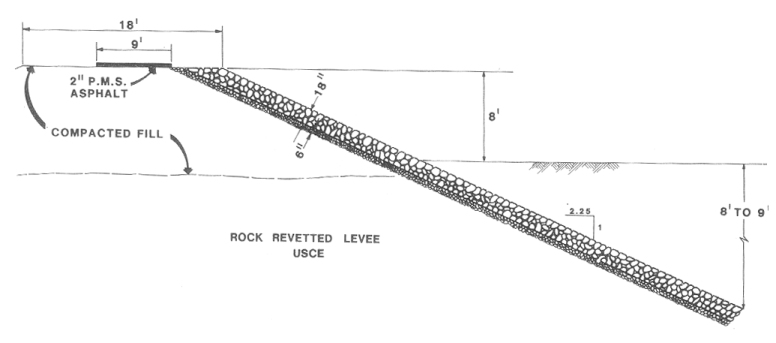

10 - The San Jacinto Levee was designed and built in Riverside

County under the auspices of the

Los Angeles District of the U.S. Corps of Engineers in 1960-61.

The levee failed in 1980, while experiencing a flow of only 29% of design-channel

capacity. A protective rip-rap apron

was designed for the river side of the levee

extending 10 feet below the channel bed, shown

in the lower inset above (Edwards, 1982). Unfortunately, the on-site materials were not

adequate to provide the proper

percolation

filter between the rip-rap and the sandy loam soils comprising the dike embankment

(Sciandrone, et al, 1982). It is likely that a helical underflow current

developed against the inside face of the levee just downstream of the turn

shown above. This downward current likely undercut the levee well below the

dry channel bed

and

succeeded in causing hydraulic piping of the levee materials through the rip-rap.

The plaintiffs tried to establish inverse condemnation sort without

showing

fault on the part of the defendant.

agency's design, construction,

or maintenance of a flood control project is shown to have posted an unreasonable

risk of harm to the plaintiffs, and such unreasonable design, construction,

or maintenance constituted a substantial cause of the damages, plaintiffs

may recover regardless of the fact that the project's purpose is to contain

the 'common enemy' of flood waters" 47 C3d at 565.

In this case, plaintiffs failed

to establish that the flood damage was the result of any unreasonable act

or omission by the defendants. Therefore,

the Supreme Court affirmed the judgment in defendants' favor.

Although Belair stands

as a landmark decision affirming the torts protecting flood control districts,

the Supreme Courts' recognition that the levee's failure at something less

than its design capacity opens a tort liability door for future plaintiffs,

especially those other than flood control districts (i.e.

reclamation districts, municipal water agencies, etc.).

DRAINAGE

EASEMENTS

The expressed purpose of most

drainage easements is for storm water drainage, including construction access

or maintenance of work, improvements, and structures, and also for the clearing

of obstructions and vegetation.

If evidence establishes that there

has never been any construction or maintenance of any works, it can

be shown that the Public Agency never exercised any dominion, or control,

over the channel ‑ thereby negating an implied acceptance cause of action.

Formal acceptance of easements

requires an ordinance or resolution of the governing legislative body which

has jurisdiction, expressly accepting the offer of dedications. See County of Inyo vs Given (1920),

183 C. 415, 191, p. 688 and Santa Clara vs Ivancovich (1941)

47 C.A. 2d 502, 188, p. 2d 303.

Generally speaking, there are

two ways that easements can be accepted via the Subdivision Map Act:

a. Public entity expressly accepts the offer

of dedication on the final map (becomes effective when map is filed) Government

Code 66477.3.

b. Official Resolution of the Public Entity

accepting an offer of dedication Government Code 66477.3.

Once there is an

offer of dedication, the offer remains open and cannot be revoked, except

as provided by statute. Government

Code 66475 and 66477.2.

Even if an offer is rejected,

the offer remains open in perpetuity and governing body may later rescind

its actions and accept the offer by appropriate resolution. Government Code 66477.2.

An agency should be careful to

check and see if the easements drawn up on improvement plans were ever

accepted and recorded. These are termed

statutory dedications, governed

by the Statutory Map Act and are exclusive of the Common Law Rules

for dedication.

In many instances, an agency such

as a water district will utilize approved development plans for purposes

of planning adjacent improvements or maintenance activity. Although approved plans usually show proffered easements, this doesn't mean

that the easements have actually been accepted. Many lawsuits are erroneously filed on the part

of plaintiffs who assume easement boundaries are in effect when, in fact,

they are not.

IMPLIED

EASEMENTS OR

IMPLIED DEDICATIONS

In the California Government Code

section directly following the provision for formal easement acceptance (GC 66477.4), a governmental

agency is prevented from disregarding an offer of dedication if it then moves

forward and uses the improvement for the public good and welfare.

The public use can theoretically be substantiated as "constructive

acceptance".

Plaintiff attorneys probing this

area of law maintain that public entities make a calculated risk decision

when they take no action or measures on the basis

of "no easement ‑ no liability exposure for loss". Any facility or activity that is clearly tinged

with public use or benefit can be theoretically construed to be a form of

constructive easement acceptance

in lieu of a formal acceptance of dedication.

The legal theory supporting this is basically constitutional, emanating

from an individual's 5th Amendment Rights to be justly compensated for governmental

usage, taking, or in the case of California,

simple damage. In this manner, an individual

is not singled out to bear the environmental or financial burden of public

agencies' decisions.

Some examples of the more interesting

implied dedication cases are presented below.

Marin

vs City of San

Rafael (1980) 111 Cal

App. 3d 591

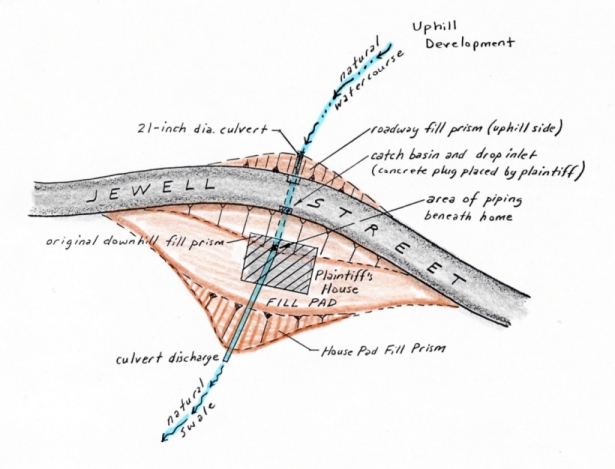

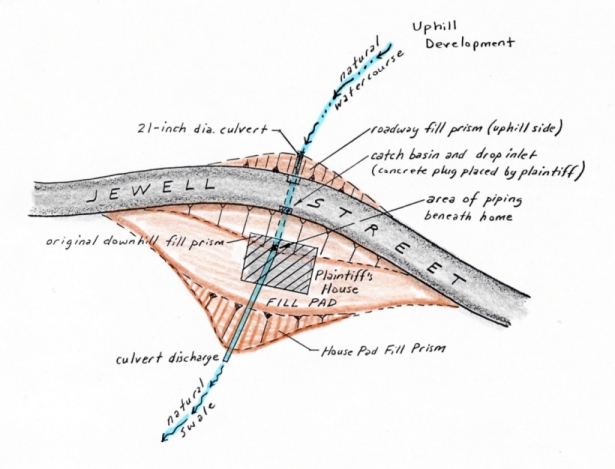

Some time prior to 1942, the City

of San Rafael required that a

12‑inch‑diameter culvert be installed along and under the surface

of newly‑constructed Jewell Street

to a point where it turned westward and continued for 12 feet onto what was

to become Marin's lot. There the culvert discharged into the natural

watercourse (gully). Around 1949, the

City began issuing building permits for another development, uphill and to

the northeast. This development increased

the demands on Jewell Street's

12‑inch culvert, so it was replaced by the City with another, 21 inches

in diameter, again extended onto Marin's yet‑to‑be‑developed

lot. The parcel owners

permission for the successive placement of the pipes had not been sought by

the City, nor was such placement objected to by the owner.

Around 1950, the parcel's owner

extended the 21‑inch pipe downhill and beyond the lot's lower and western

boundary, backfilling with fill over the pipe to create a more level development

pad. This placement had been accomplished

with the knowledge and even advice of a City employee, the City even providing

the fill.

In 1952, a home was constructed

on the lot over the buried 23‑inch drainage pipe (see Figure 11). A building permit had been issued by the City.

The plaintiffs (Marins) purchased the home 21 years later, in 1973.

They had not been informed of any storm drain line or culvert beneath

the property. Twenty‑one months later, water gushed

up into the basement due to the pipe being filled to over capacity. The plaintiffs asked the City to take care of

the problem and were told that "it was a private problem, and, as far

as they were concerned, the pipe didn't exist, it was up to the homeowner

to take care of it".

Figure 11

- In Marin vs. San Rafael,

a road fill (1942), culvert (1949), fill pad (1950), and home (1952) were

constructed upon and across a topographic swale

containing a natural

watercourse. The City’s cross-road culvert had been extended across the lot

to accommodate fill for the house pad with the City’s knowledge

in 1950. In 1975,

the homeowner (Marin) began to notice foundation soils collapsing over the

culvert extension during peak run-off events. The City denied

responsibility for

maintenance or repair, saying “as far as they are concerned, the pipe doesn’t

exist”. Marin then blocked the pipe with concrete, therein

causing a back-up

of run-off behind the roadway fill prism,

which flooded onto Jewell Street!

Marin prevailed in Court in an inverse condemnation

action against the

City under the doctrine of easement implied by usage.

The plaintiffs responded by placing

a "concrete obstruction" in and above the rupture to the pipe "in

order to prevent further damage to their property". The City then sought an injunction compelling

plaintiffs "to remove the concrete plug from this storm drain and to

restore the storm drainage system to a condition that is operational ....."

Although the court supported the

City's defense, the Appeal Court

reversed, ruling that the plaintiff's property had suffered physical damage

proximately caused by a public improvement or public use maintained as deliberately

planned and designed by the City. The

Appeal Court further

found that none of the plaintiff's damages were caused by their own act, or

fault, or negligence.

Chatman

vs Alameda County Flood Control District (1986) 183 CA 3d 424

A similar series of events were

tested in the case of Chatman vs Oakland

(1988) and Chatman vs Alameda County

Flood Control and Water Conservation District (1986) 183 Cal App 3d 424.

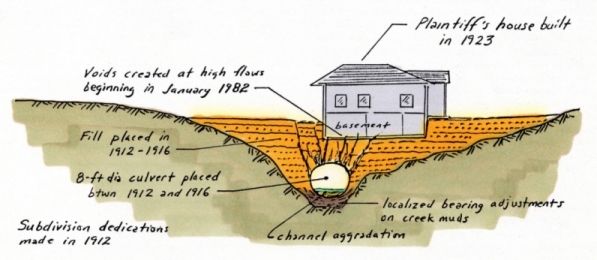

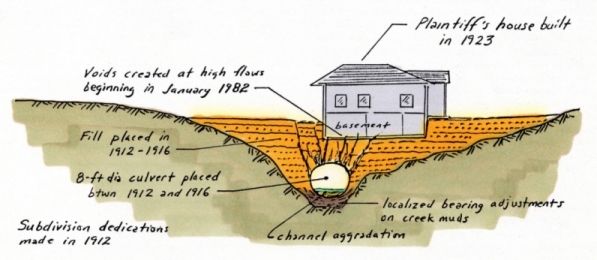

In this case, a hillside area was subdivided in east Oakland

between 1912 and 1916. At that time,

a culvert was placed across Lyon Creek and backfilled with fill to allow a

road crossing. The culvert was then extended and backfilled

to create a buildable lot which was subsequently developed in 1923. Chatman moved into the house in 1965 and began

to notice settlement beneath her home during a peak run‑off period in

January, 1982. An inspection of the

old culvert beneath her property revealed that it had become cracked and that

soil backfill was piping into the culvert during periods of high flow. The resulting soil cavities were then collapsing,

undermining the Chatman home (see Figure 12).

As in the case

of Marin, both the City and the local flood control district disputed responsibility

on the basis of ownership versus use. The culvert section beneath Chatman did not

lie within an accepted easement and the line was considered to be privately

owned, and therefore, privately maintained.

The Flood Control District eventually prevailed in their defense because

the plaintiff had allegedly implied dedication through annual inspections

begun by the District in 1963. The

Court held that, although the District knew of the dangerous condition of

the culvert through its inspections, it

could not be held liable for damage caused by the culvert unless it had owned,

controlled, constructed, repaired, or maintained the culvert. There was no discussion by the Court as to whether

the District had a responsibility to inform the affected property owners of the damaged culvert as soon

as the District learned of its condition.

However, in the remaining suit against the City of Oakland,

Chatman eventually prevailed (see Cal Jury Verdicts, V. 32, n. 32, Aug. 5, 1988). The Court ruled that the public benefited from

the culvert section within the Chatman property. After all, had Chatman blocked the culvert or

filled it in (as Marin did) grievous flood damage would have resulted to the

surrounding neighborhood. The City

had also exerted control in the

letting of building permits, allowing for the construction of a home over

the culvert. Oakland

countered by maintaining that the creek was not a natural watercourse, but

a man‑made channel constructed for the homeowners' benefit and convenience.

This would appear to have been an incompetent defense as Lyon Creek

is one of the earliest mapped landmarks in the East Bay, having formed the

land‑grant boundary between Ignacio and Antonio Maria Peralta in 1820

(one of the four original land grants in the San Francisco East Bay).

The Court ruled in favor of the plaintiff.

Figure 12

Figure13

- In the case of Chatman vs. Oakland

(1988), a plaintiff in the inverse condemnation action alleged implied dedication

of their own 8-foot-diameter

culvert on the basis

of its continual usage, benefiting the public welfare. Although the plaintiff

prevailed again the City, it lost and earlier inverse suit against

the

County Flood Control District on the basis of inspections being grounds for

inverse tort. The city’s assertion that Lyon Creek was not a natural watercourse

was unfounded based

upon early maps of the region (above).

BURDEN

OF PROOF OF "PUBLIC USE”

In many other cases, plaintiffs

have been less successful in alleging that there was sufficient public use

or benefit of improvements made on private property. In the case of Cantu vs PG&E (1987) 189 Cal

App 3d 160, plaintiffs purchased a lot in a 16‑unit subdivision with

private drives for access. Before any

of the lots were sold, PG&E had installed an 18‑inch‑wide,

6‑foot deep utility trench for gas, electricity, and telephone.

The plaintiff's property experienced

a landslide during the winter of 1980‑81 that their expert alleged was

due, in part, to the collection of water in the PG&E utility trench. Plaintiff sued PG&E under theories of inverse

condemnation, trespass, and nuisance. The

trial court found defendant inversely liable and rejected PG&E's defense

of comparative negligence. The jury

upheld PG&E's defense on the trespass and nuisance actions and returned

a verdict of no damages for plaintiff.

The court found that utility districts

have the legal right to:

a. Condemn lands to furnish utilities for customers; or

b. Operate and maintain lines along private

property without condemning property.

In the Cantu's case, PG&E

did not condemn the property nor did they condemn the land in an eminent

domain proceeding.

The Court concluded by stating

that "the law of inverse condemnation, viewed broadly and in perspective,

seeks to identify the extent to which otherwise uncompensated private losses

attributable to governmental activity should be socialized and distributed

over the taxpayers at large rather than borne by the injured individual"

(quoted from Val Alstyne, 1969.) The

court, after citing this language, held that the trench did not benefit the

public at large and that the running of line extensions to plaintiffs' residence

was not the type of quasi‑public activity where the risk of injury should

be spread over society.

CONCLUSIONS

Inverse condemnation proceedings

are supported in theory by individual rights of government compensation for

the taking or damaging of property. In

most instances, the public agency has caused unintentional physical damage

to property. Liability in inverse condemnation

for unintended physical damage is proper when the damage resulted from a public

entity's ownership, maintenance and/or use of a public improvement.

When a public agency fails to construct or maintain its improvement

properly, it takes a calculated risk that damage to private property may occur.

If damage to private property results, it is proper to require the

entity that took this risk to bear the loss when damage occurs.

The "Reasonable Use"

rule that has applied to surface waters since the Keys/Romley Case of 1966 was recently upheld in the California Supreme

Court decision in the Locklin case. As a consequence, the "Common Enemy Doctrine"

only affords protection insofar as the actions taken by someone to protect

their property can be deemed “reasonable”, as constructed and as maintained.

There is little question about

liability in the case of buried improvements, such as culverts or pipes ‑‑

whoever owns these is strictly liable for the damage they cause. However, recent decisions have served to extend

such liability to those sections of buried conduit that are privately owned,

but through which "public agency waters" may flow or be diverted

to. We can expect the area of "Implied

Dedication" suits to enlarge over the coming decade because private insurance

carriers have extensively modified their policies to exempt all manner and

form of flood or earth movement losses. If the damaged property is aged enough to be

beyond applicable statutes of limitations for patent or latent

defects, the public agency becomes the only entity with which to file suit.

According to many recent cases

in California, public entities may be liable under inverse condemnation for

any damages to property caused by a public improvement as deliberately designed

and constructed, regardless of any fault

or negligence by the Agency (see Olshansky, 1989, p. 110).

As the cost of litigation continues

its skyward acceleration in California

,

the burden will have to be spread back to the consumer via the embattled

agencies. Flood peril is the only nationally

adjudicated program which provides protection and relief from this type of

natural disaster. But, NFIP proceeds

only pay for a single occurrence of flooding, after this the parcel owner

must raise their floors to be above the 100-year or 500-year inundation levels.

No other systematic system of insurance exists to accommodate the

potentially prodigious losses that will be posed by massive

infrastructure aging/corrosion, earth movement, environmental pollution

(such as selenium), or earthquakes. Each of these could easily spawn losses in the

billions of dollars, the likes of which are probably not yet well appreciated

by decision makers.

REFERENCES

Bull, W.B., 1991,

Geomorphic Response to Climatic Change: Oxford

University Press, New

York, 326 p.

California Council of Civil Engineers and Land Surveyors,

1981, Drainage Law Syllabus, prepared by Turner and Sullivan, Sacramento,

Short Course Notes, 82 p.

Edwards, K. L., 1982, Failure of the San Jacinto River Levees

Near San Jacinto, California, From

the Floods of February 1980: in Storms, Floods and Debris Flows in Southern

California and Arizona in 1978 and 1980:

National Research

Council, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pp. 347-356.

McGuire, J.F., and Noziska, C.B., 1988, Landslide and Subsidence Liability

Supplement, March 1988; Calif Continuing Education of the Bar, Supplement

to California Practice Book No. 65, Berkeley, 182 p.

Morgan, A. E., 1952, The Miami Conservancy

District: McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York,

502 p.

Olshansky, R.B. and Rogers, J.D., 1987, Unstable Ground: Landslide

Policy in the United States:

Ecology Law Quarterly, V. 13, n. 4, pp. 939‑1006.

Olshansky, R.B., 1989, Landslide Hazard Reduction: A Need

for Greater Government Involvement: Zoning and Planning Law Report, V. 12,

n. 3 (March) pp. 105‑112.

Olshansky, R.B., and Rogers, J.D., 1992, The concept of reasonable

care on unstable hillsides: in Slosson, J.E., Keene, A.G., and Johnson, J.A.,

eds., Landslides/landslide Mitigation: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society

of America

Reviews in Engineering Geology, v. IX, pp. 23-27.

Rogers, J.D., Pleistocene to Holocene

Transition in Contra Costa County, California: in Geology of San Ramon and

Environs, Northern California Geological Society Field Trip Guidebook, ed.

R. Crane, pp. 29-52.

Shuirman, G., and Slosson, J.E., 1993, Forensic Engineering:

Academic Press, San Diego, 256

p.

Sutter, J.H. and Hecht, M.L., 1974, Landslide and Subsidence

Liability: California Continuing

Education of the Bar California

Practice Book No. 65, Berkeley,

240 p.

Slossen, J.E., McArthur, R.C., and Shuirman, G., 1987, Legal

Misuse of Urban Hydrology Concepts and Regulations for Rural Areas; Engineering

and Hydrology Proceedings, Hydrology Division, Am. Soc. Civil

Engineers,

Williamsburg, VA, Aug. 3‑7, 1987, pp. 714‑719.

Sciandrone, J., Albrecht, T., Davidson, R., Douma, J., Hammer,

D., Hooppaw, C. and Robles, A., 1982, Levee Failures and Distress, San Jacinto

River and Bautista Creek Channel, Riverside County, Santa Ana River

Basin,

California: in Storms, Floods and Debris Flows in Southern California and

Arizona in 1978 and 1980: National Research Council, National Academy Press,

Washington, D.C., pp. 357-385

Van Alstyne, Arlo, 1969, Inverse Condemnation: Unintended

Physical Damage: Hastings Law

Journal, V. 20, n. 1 (January), pp. 431‑516.

V.T. Chow and N. Takase, 1977, Design Criteria for Hydrologic

Extremes: Journal of the Hydraulics Division, Am. Soc. Civil Eng’rs, v. 103,

n. HY4 (April), pp. 425-36.

presented at the San Francisco Insurance

Claims Forum in San Francisco, April

16, 1997

J. David Rogers is the Karl F. Hasselmann

Missouri

Chair in Geological Engineering

at the Missouri University of Science & Technology. He

received his B.S. in geology from the

California State Polytechnic University

in 1976, M.S. in civil engineering from U.C. Berkeley

(1979) and Ph.D. in geological and geotechnical engineering from U.C. Berkeley

in 1982. Between 1979-2001 he served

as a principal with three different geotechnical consulting firms and from

1994-2001 he served on the faculty of the Department of Civil & Environmental

Engineering at the University of California at Berkeley. His career has focused on natural disasters

associated with earth movement, floods and earthquakes. The author of over

100 articles, he is a recipient of the Rock Mechanics Award of the National

Research Council, the E.B. Burwell Award of the Geological Society of America

and the R.H. Jahns Distinguished Lecturer Award

of the Association of Engineering Geologists and Geological Society of America,

for his contributions to geoforensics,

with particular emphasis on the failure of dams and levees. He can be reached at rogersda@mst.edu

Questions or comments

on this page?

E-mail Dr. J David Rogers at rogersda@mst.edu.